GALAXY SOHO, Zaha Hadid Architects

- Mark Lafond, RA

- 6 days ago

- 8 min read

Sustainable Change Models of Innovation

Project Overview

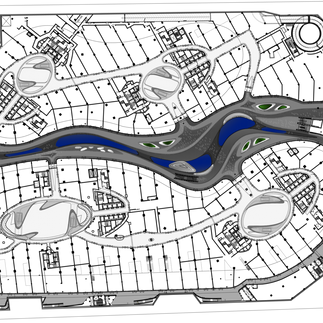

Galaxy SOHO is a large scale office, retail, and entertainment complex in central Beijing, commissioned by SOHO China and designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. Completed in 2012 after a multi year design and construction period, the project sits near Chaoyangmen on Beijing’s East Second Ring Road, a dense urban condition where continuity of pedestrian movement, access, and internal circulation often determines whether a commercial development behaves like an isolated object or a working piece of city fabric.[1.]

Zaha Hadid Architects framed Galaxy SOHO as an interior urban landscape, a building that generates its own network of streets, courts, and connective bridges rather than relying on a single monumental atrium. The project’s published data emphasizes its size and program distribution: 332,857 square meters of total floor area on a 46,965 square meter plot, with four above ground towers organized across 15 floors, plus below ground retail and parking levels accommodating 1,275 cars.[1.]

In SOHO China’s 2012 annual report, the company also describes the project as an “iconic commercial development” within the Second Ring Road, noting that it was completed and delivered in November 2012.[2.]

Site, Urban Role, and Access Logic

Galaxy SOHO’s location is both its advantage and its constraint. The East Second Ring Road is a powerful address and transport corridor, but also a place where large footprints can sever finer grain circulation patterns if they do not provide multiple points of entry and legible internal routes. Zaha Hadid Architects responded by organizing the project as a cluster of volumes that shape a sequence of open courts and passages. In other words, the “front door” is not a single ceremonial entry, it is distributed. That matters for mixed use performance: office users, retail visitors, service flows, and after hours restaurant traffic are different populations with different schedules and security needs. A distributed access concept gives operators more flexibility to zone circulation and manage time based occupancy without shutting down the whole complex.[1.]

The project narrative also links form to the courtyard tradition, not as a literal historical imitation, but as a spatial strategy: courts create address points, daylight, orientation, and a hierarchy of public to semi public space. Zaha Hadid Architects describes the building as a reinvention of interior courts that produces “continuous open spaces,” and an immersive experience “at the heart of Beijing.”[1.]

Whether one reads that as urban generosity or as a controlled private city, the design intent is clear: the public realm is pulled inside and made continuous with the building’s circulation.

Architectural Form and Spatial Experience

Galaxy SOHO is defined by continuous curvilinear geometry and the absence of hard corners in its primary public spaces. Rather than stacking rectilinear floor plates, the project uses layered, rounded bands that read as horizontal strata wrapping each volume. Bridges and stretched connections link the towers, allowing movement between volumes at multiple levels and producing framed views across the courts.[1.]

The most important experiential effect is that navigation is not linear, it is sequential. Users discover spaces by moving deeper into the complex, with visual cues created by curvature, vertical voids, and connective bridges.

A key operational advantage of this geometry is that it supports many “addresses” within one development. Retail frontages can face courts, ramps, and internal streets, rather than being limited to a perimeter mall condition. That can increase leasing resilience because operators can curate zones with different foot traffic intensity. It also supports event programming, pop ups, and seasonal activations in the courts, which is one reason Galaxy SOHO has been recognized for public space qualities in later awards coverage.[4.]

Program Stack and Mixed Use Performance

Zaha Hadid Architects publishes a clear program stack: the lower three levels contain retail and entertainment functions, the levels above provide work spaces, and upper levels host bars, restaurants, and cafes.[1.] This vertical separation aligns with common commercial logic in dense cities: high turnover public functions near grade, longer dwell office space above, and destination hospitality at the top where views become a value driver.

SOHO China’s disclosures provide additional insight into how the project was monetized. The company launched pre sale on June 26, 2010, and by December 31, 2012 it reported cumulative contract sales of approximately RMB 16,173 million, with average selling prices reported separately for office and retail areas.[2.]

Importantly, SOHO China also retained approximately 34,096 square meters of lettable area as investment property.[2.] That split between sold strata and retained income producing area is a strategic choice that affects building systems and operations: retained areas are typically managed under a consistent property management regime, while sold strata can introduce fragmented tenant standards unless governance and fit out controls are strong.

Technology in the Design Process

Galaxy SOHO is a highly geometric building, and its delivery depends on precise coordination between architecture, structure, envelope, and MEP routing. While Zaha Hadid Architects’ public materials do not publish a full BIM execution plan, the project credits, team listing, and built outcome point to a workflow where digital modeling is not optional, it is the core instrument for geometry control and clash avoidance.[1.]

ArchDaily’s project documentation lists BIAD, Beijing Institute of Architecture and Design, as the local design institute, indicating a collaboration structure typical for large projects in China, where international design authorship is translated into local codes, documentation, and construction administration in partnership with a domestic institute.[5.]

That technical interface is itself a kind of “technology,” because the project’s complex geometry must become buildable details, tolerances, and sequences that contractors can execute reliably.

Envelope Strategy and Building Services Interface

Zaha Hadid Architects’ published information emphasizes continuous exterior surfaces and panoramic interior conditions, which implies an envelope designed to support long runs of curved curtain wall and consistent thermal performance across non orthogonal geometry.[1.]

Even without a published wall section schedule, the major technical issue is straightforward: curved geometry increases the risk of custom fabrication and tolerance stacking, so the envelope must balance design continuity with a rationalized panel system and repeatable modules.

The Zaha Hadid Architects data also explicitly calls out MEP scope for retail floors totaling approximately 90,000 square meters.[1.]

Retail MEP loads are typically heavier than office loads, due to ventilation requirements, kitchen exhaust for food tenants, higher lighting densities, and variable occupant loads. Calling out retail MEP area signals how much of the project’s technical complexity is concentrated in the public base, where systems must support constant change in tenant fit outs over time.

Smart Building Features and Operational Intelligence

Public sources for Galaxy SOHO focus on architectural form, urban space, and commercial scale, and they do not publish a detailed smart building specification or a named building management system platform.[1.][2.] In the absence of project specific control schedules, the most defensible way to describe “smart building” capability is to define the operational layers that a complex of this type must have to function safely and efficiently, and to distinguish them from claims of advanced automation.

For a multi tower, mixed use commercial complex with below grade retail and two parking levels, operational intelligence typically concentrates in six systems domains:

Centralized monitoring and alarms for life safety systems, including smoke control interfaces for large interconnected public spaces and below grade areas.

HVAC control logic that can handle multiple occupancy profiles, retail peak loads, and tenant controlled zones, while maintaining stable conditions in common circulation courts.

Lighting control in public zones, where scheduling, occupancy sensing, and daylight response can reduce operating costs and improve consistency in wayfinding.

Security and access control capable of separating office circulation from late night hospitality use, and of supporting event based crowd management in the courts.

Vertical transportation monitoring, especially where bridges and multiple levels create non standard movement patterns that can shift peak demand away from simple morning and evening office peaks.

Energy metering and submetering for tenant billing and operational benchmarking, particularly important when part of the project is retained as investment property and part is sold as strata.[2.]

These functions do not require speculative claims about futuristic automation. They are the baseline “smart” stack for a building where geometry and mixed use intensity create real operational complexity. The innovation is less about novelty devices, and more about integrating monitoring, zoning, and control so that the architecture’s continuous public realm remains comfortable, safe, and commercially productive across changing tenant mixes.

Innovation, Recognition, and Debate

Galaxy SOHO’s innovations sit at the intersection of spatial continuity and urban interiority. It was recognized by the Royal Institute of British Architects with an International RIBA Award in 2013, as noted by Zaha Hadid Architects in its awards announcement.[3.] The project later received recognition in China, including an award from the Architectural Society of China and a “Best Public Space” designation in a Chinese interior design awards program, again reported by Zaha Hadid Architects.[4.]

The same qualities that made it a global design icon also placed it in the middle of debate about development impacts in Beijing’s historic urban fabric. Reporting in international media documented criticism from preservation advocates in relation to the project’s context and the symbolism of awarding it.[6.] For an owner operator and for the city, that tension matters because landmark status is not only aesthetic, it affects leasing identity, visitor behavior, and long term positioning in a competitive commercial market.

Construction Costs and Specifications

Construction cost information for Galaxy SOHO is not published as a single line item “construction cost” figure in the publicly available project pages from Zaha Hadid Architects, and SOHO China’s 2012 annual report discusses the project’s sales performance and delivery rather than isolating a stand alone construction cost total for this one asset.[1.][2.]

The most reliable publicly documented financial figures tied directly to Galaxy SOHO in SOHO China’s disclosures are its cumulative contract sales and average selling prices, plus the company’s retained lettable area.[2.]

Construction cost, and related project financial figures, as publicly documented:

Cumulative contract sales by December 31, 2012: approximately RMB 16,173 million.[2.]

Average selling price by December 31, 2012: approximately RMB 63,634 per square meter for office area, and RMB 86,311 per square meter for retail area.[2.]

Retained lettable area kept by SOHO China as investment property: approximately 34,096 square meters.[2.]

Group wide cost of properties sold in 2012: RMB 6,298,439,000, reported by SOHO China for the year, not isolated to Galaxy SOHO alone.[2.]

Project specifications, enumerated:

Project name: Galaxy SOHO.[1.]

Architect: Zaha Hadid Architects.[1.]

Design attribution: Zaha Hadid with Patrik Schumacher.[1.]

Client, developer: SOHO China Ltd.[1.][2.]

Location: Beijing, China, Chaoyangmen area on the East Second Ring Road corridor.[1.][2.]

Project dates: 2009 to 2012, built.[1.]

Total floor area: 332,857 square meters.[1.]

Plot area: 46,965 square meters.[1.]

Above ground massing: 4 towers, 15 floors total, consisting of 12 office floors and 3 retail floors.[1.]

Maximum height: 67 meters.[1.]

Below ground program: B1 retail, B2 and B3 parking.[1.]

Parking capacity: 1,275 cars.[1.]

Retail MEP scope noted in project data: retail floors B1, 1, 2, 3 totaling approximately 90,000 square meters.[1.]

Delivery milestone: completed and delivered in November 2012, as reported by SOHO China.[2.]

Local design institute reported in published project documentation: BIAD, Beijing Institute of Architecture and Design.[5.]

WORKS CITED

[1.] Zaha Hadid Architects. “Galaxy SOHO.” Zaha Hadid Architects, 2009–2012.

[2.] SOHO China Limited. Annual Report 2012. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, 12 Apr. 2013.

[3.] Zaha Hadid Architects. “Pierresvives and Galaxy Soho win RIBA Awards 2013.” Zaha Hadid Architects, 18 June 2013.

[4.] Zaha Hadid Architects. “Galaxy SOHO awarded by the Architectural Society of China.” Zaha Hadid Architects, 2 Dec. 2014.

[5.] ArchDaily. “Galaxy SOHO / Zaha Hadid Architects.” ArchDaily, 29 Oct. 2012.

[6.] Wainwright, Oliver. “Zaha Hadid’s Mega Mall Accused of ‘Destroying’ Beijing’s Heritage.” The Guardian, 2 Aug. 2013.

_______________________________________________________________________________